Author: Heather Deck

Climate Change

April 5, 2023

Climate Change

It’s not an if. It’s a when. That’s how many people in our watersheds approach the idea of the next devastating storm.

In 2018, a category 1 Hurricane Florence made landfall just south of Wrightsville Beach, and in the days that followed, became one of the most devastating hurricanes on the North Carolina record.

Florence delivered up to 30 inches of rain in many places; freshwater flooding due to the torrential rain led to hundreds of people being rescued from homes farther inland; historic storm surge in New Bern and Washington did the same. More than 4,300 eastern North Carolina homes were damaged or destroyed. On the Neuse, Trent and Cape Fear rivers, 46 industrial swine and 35 poultry facilities flooded, sweeping tons of waste into local waterways, and coal ash spilled from the Neuse floodplain.

Just two years prior, Hurricane Matthew delivered similar destruction.

These two, 500-year storms hit North Carolina within a 23-month period.

This is climate change.

A key impact of climate change is more storms, wetter storms — not limited to hurricanes and tropical systems, but everyday storms. Magnified by sea-level rise, flooding from these storms is severely affecting just about every aspect of life. It destroys buildings, homes, land and crops, endangered species and critical habitats; disrupts business operations and economic activity; threatens our roads, resources and energy and water utilities. It results in more water pollution, highlights social inequalities and how difficult it is for rural, lower-income counties to adapt to a greater flooding threat.

And according to North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality’s Climate Risk Assessment and Resilience Plan, released in 2020, the state should plan for greater extremes in the future. We may not be able to stop the impacts of climate change, but what we can do is be more resilient to them.

Read the 2020 North Carolina Climate Science report on the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality website.

Ways We Can Be Resilient

Wetlands: protecting our wetlands is key to flood mitigation. Where levees and sea walls simply attempt to block incoming floodwater, wetlands naturally decrease destructive wave action, spread water out and ultimately filter the water, removing harmful pollutants.

Living Shorelines: constructing/restoring living shorelines means habitat is restored, our coast is protected from erosion and damage from storms, water quality is improved and recreational opportunities such as fishing, swimming and public access abound.

Swine Buyout Plan: in North Carolina, hogs outnumber people in 30 of our 100 counties, many of which are located in floodplains and on the banks of the rivers and creeks of eastern North Carolina. When it floods, there’s no place for those tens of thousands of hogs and their millions of gallons waste to go — except into the waterways. North Carolina has a Swine Buyout Program, intended to buy out those swine facilities in the floodplain, and the land used for other purposes such as growing crops. It’s a popular program that had 138 applications and a total of 43 facilities bought out until it was effectually halted. How? Funding for the Swine Buyout Program is continually removed from the budget during the North Carolina General Assembly’s budget negotiations.

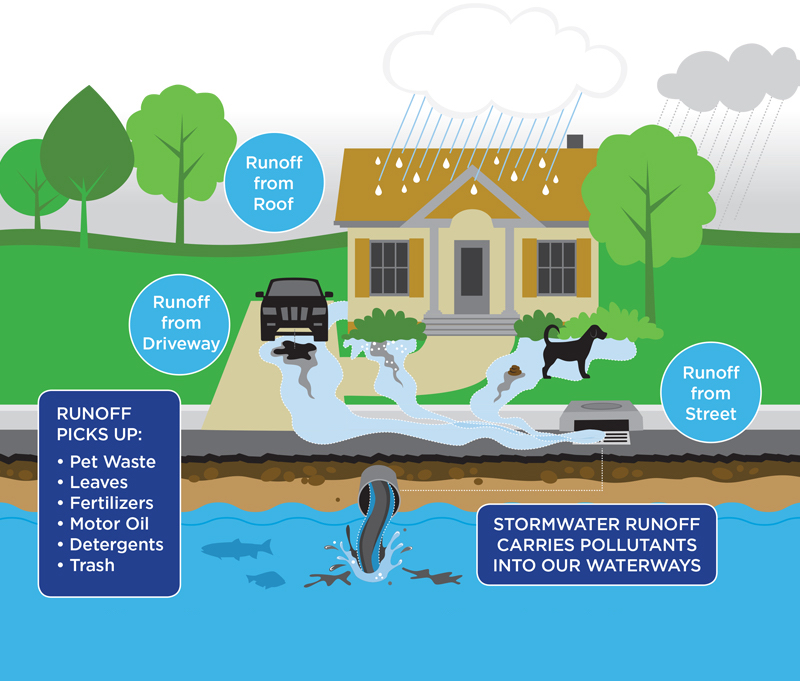

Watershed restoration plans: Watershed restoration plans are an important element of resiliency. These plans identify pollutant sources and land-use changes in the watershed, and make of list of priorities that will restore habitat and water quality. Stormwater runoff reduction measures installed through watershed plans have been shown to greatly reduce bacteria and sediment in polluted runoff from storms.

Latest News

Wayne Community College wetland passes first test(s)

January 11th 2024

ACTION ALERT: NCDEQ permits need OUR input!

October 26th 2023

Riverkeeper introduced to aerial investigation

October 26th 2023

Neuse Riverkeeper goes on the record about CAFO pollution

October 19th 2023

Aerial tour reveals major Neuse pollution threats

October 5th 2023

Ophelia brings unexpected impacts

September 28th 2023

Washington gets a stormwater scouting

September 21st 2023

Sound Rivers team tracks Neuse fish kill

September 14th 2023

Tour a Sound Rivers constructed wetland with Clay

September 14th 2023

Microplastics

April 5, 2023

Microplastics

Plastics end up in our waterways all the time, whether it’s through roadside litter washed into a creek during a hard rain or people using our precious natural resources as convenient dumping grounds. Plastics do break down, and when they do, it’s into microscopic pieces called microplastics.

Less than 5 mm in size, microplastic pollution can only be seen under a microscope. Sometimes they are small fibers, sometimes they are microbeads, other times they are films or flakes. They don’t go away — they just break down into smaller and smaller pieces.

Since they’re so tiny, microplastics can be ingested by and build up in aquatic life, which means we can end up ingesting plastic, too.

Sound Rivers is engaged in a statewide research project to determine how macroplastics end up in our waterways, how they break down into microplastics, impacts on waterways, wildlife and public health and what we can do to prevent this type of pollution.

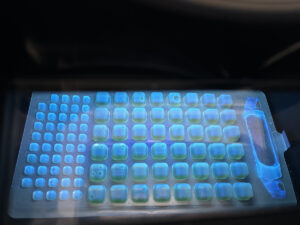

Part of the project is Sound Rivers’ Riverkeepers and Water-Quality Specialist collecting water samples from local waterways to be boiled down, filtered and viewed under a microscope for the presence of microplastics.

Another part of the projects is Sound Rivers’ three Trash Trouts, or litter-trapping devices, installed on waterways in the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico river basins, that are also informing the “bigger picture” aspect of study: each Trash Trout is monitored and cleaned out regularly, and its contents audited by volunteers to see just where the microplastics are coming from. These Trash Trouts are located on Jack’s Creek in Washington, Duffyfield Canal in New Bern and Little Rock Creek in Raleigh.

Latest News

Small cleanup, with a big impact

April 25th 2024

New trash trap gets adjustment, first cleanout

April 4th 2024

Trash trap No. 5 makes Greenville debut

March 28th 2024

Coming soon! Greenville trash trap

March 14th 2024

Sound Rivers trash traps pass Tropical Storm Idalia test

September 7th 2023

Stormwater Runoff

April 5, 2023

Stormwater Runoff

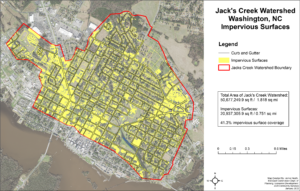

When rain falls in a natural setting, almost all stormwater infiltrates the soils and groundwater or is taken up by vegetation. But when land is developed, the impervious cover (roads, rooftops, driveways, parking lots) increases the volume of stormwater that is not absorbed by the land and accelerates the transport of stormwater across the surface of the land. As impervious cover increases, so does the volume and velocity of contaminated surface runoff into streams, lakes and sounds.

Polluted stormwater runoff, including sediment from poorly maintained construction sites, is the number one reason for poor water quality in North Carolina and one of the main causes of pollution in the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico rivers. Sediment can cause severe problems for creeks, rivers and estuaries on which we depend for our drinking water, recreation, wildlife habitat and fishing.

Stormwater pollution results in a multitude of economic losses. Sediment, toxic pollutants and pathogens in stormwater leads to poor quality fish catch and financial losses for the commercial and recreational fishing industries. Contaminated beaches result in medical expenses for treating water-related illness, and the coastal community suffers from losses in sales and services. Stormwater pollution also leads to increased water treatment costs.

When stormwater runoff increases, it can create significant flood damage repair costs and dredging costs, as sediment washed from the land settles in our waterways.

Yet, measures to decrease stormwater impacts can significantly increase property values.

Read about ways you can decrease and/or treat stormwater runoff on your own property on our Protecting Water Quality At Home page!

Learn about Sound Rivers’ green stormwater infrastructure projects at schools across the Tar-Pamlico and Neuse watersheds here.

Latest News

Riverkeepers eye pollution sources from the sky

May 9th 2024

Riverkeeper, association partner for Ellerbe Creek monitoring

May 2nd 2024

Durham turns down Lick Creek development

April 25th 2024

Scout earns volunteer hours with trash trap cleanout

April 25th 2024

Position available: Stormwater Education Coordinator

April 18th 2024

Southern Nash next in line for stormwater projects

April 18th 2024

Feedback needed for Jack’s Creek plans, projects

April 11th 2024

New cistern project on go

April 11th 2024

New trash trap gets adjustment, first cleanout

April 4th 2024

Sanitary Sewer Overflows

March 29, 2023

Sanitary Sewer Overflows

Sanitary sewer systems collect and transport domestic, commercial and industrial wastewater, as well as limited amounts of stormwater and infiltrated ground water to treatment facilities for appropriate treatment.

Occasionally, sanitary sewers will spill raw sewage. These types of spills are called sanitary sewer overflows. SSOs can contaminate our waterways, causing serious water-quality problems and back up into homes, causing property damage and threatening public health.

How? Well, raw sewage carries bacteria, viruses, parasitic organisms, intestinal worms, molds and fungi. As a result, it can cause diseases ranging in severity from mild gastroenteritis (causing stomach cramps and diarrhea) to life-threatening ailments such as cholera, dysentery, infections hepatitis and severe gastroenteritis, according to the EPA website.

In the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico watersheds, the main cause of SSOs is predominantly stormwater and/or groundwater overloading a system during tropical weather events, or even a hard rain. Aging sewer infrastructure and new development creating an additional burden on already insufficient infrastructure also contribute to our SSOs. When you have many municipalities, and municipal sewer systems, along the banks of your rivers, the chance that something will go wrong — a pump breaks, a blockage occurs — increases exponentially, as does the chance pollution will pour into our waterways, thousands of gallons at a time.

All that bad stuff entering our rivers, lakes, streams or brackish waters can impact water quality — and not for the better. If we can’t use waterbodies for drinking water, shellfish harvesting, fishing or recreation, that’s a loss: SSOs can close beaches; tourism and waterfront home values may fall; fishing and shellfish harvesting may be restricted or halted.

So how can SSOs be reduced or eliminated?

Investment. According to the EPA, our nation’s sewers are worth a total of more than $1 trillion. Sewer rehabilitation to reduce or eliminate SSOs can be expensive, but the cost must be weighed against the value of the collection system asset and the added costs if this asset is allowed to further deteriorate. Ongoing maintenance and rehabilitation add value to the original investment by maintaining the system’s capacity and extending its life.

What can we do to reduce SSOs? Don’t pour fats, oils or grease down the sink, and don’t flush household items such as baby wipes, facial wipes, sanitary pads and tampons down the toilet—all can contribute to blockages in the system.

Let’s not forget about septic systems, too. If not installed and maintained properly, a septic system can contaminate surface and/or groundwater. If you have a septic system, learn how you can protect local surface water here.

Latest News

Havelock experiences largest spill yet

March 7th 2024

Riverkeeper tracks Rocky Mount spill site

March 7th 2024

Kinston follows through with pollution solution

February 22nd 2024

Crowd turns out for Sound Rivers-Havelock town hall

February 22nd 2024

Sampling confirms Slocum Creek pollution source

February 15th 2024

NCDEQ: 'Significant' sewage spill on Slocum Creek

January 18th 2024

Results: Rocky Mount spill definitely raw sewage

January 11th 2024

Riverkeeper hunting source of Kinston pollution

November 16th 2023

Little Rock Creek subject of water-quality study

October 5th 2023

CAFOs

March 28, 2023

CAFOs

Swine CAFOs

Among the biggest threats to water quality in both watersheds — and particularly in the lower Neuse — is large quantities of nutrient pollution, especially nitrogen and phosphorus. This type of pollution comes from a variety of sources: runoff from large areas that contain fertilizers, animal waste washed from lawns, urban developed areas and farm fields among them.

However, industrial meat production facilities, including swine and poultry facilities housing tens of thousands of animals, contribute most of the excess nitrogen and phosphorous discharging into our rivers and streams.

These facilities are called CAFOs, which stands for concentrated animal feeding operations. In North Carolina, hogs outnumber people in 30 of 100 counties, many of them rural — many of them in the Neuse and, to a lesser extent, the Tar-Pamlico watersheds. Many of them are located near or in disproportionately low-income and communities of color. And some of them are located on the banks of waterways, in eastern North Carolina floodplains.

Where a concentrated number of animals are being housed and fed, the animals are also producing waste — and a lot of it. It’s estimated that hogs put out about 10 billion gallons of waste each year, and that’s just in North Carolina. Hog waste is stored in “lagoons,” some of which are not lined, and waste can, conceivably, make its way into groundwater by soaking through the soil.

The way hog waste is disposed of is by siphoning it from the lagoon into a truck with a sprayer, and spraying the waste onto fields. This, in itself, is problematic. Spraying fields with waste can affect the air quality of neighboring communities — not only creating an awful stench, but airborne particles from this practice have been proven to have a negative impact on human health with consistent exposure. And when it rains, hog waste on fields potentially becomes stormwater runoff from those fields, washing into ditches, streams, creeks and rivers — thus, the excessive nutrients.

Some nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorous can be beneficial to aquatic life in small amounts, but large amounts can contribute to excessive plant growth, algae blooms and low levels of dissolved oxygen in the water. All that often adds up to fish kills, in which hundreds, if not thousands, of fish die and decay and add a bunch of bacteria to the mix. Nobody wants to swim or boat with dead fish. No one wants to eat a fish with sores, either.

Here’s another effect of climate change: heavier rains mean more excess nutrients are washing into the waterways. More frequent tropical storms and hurricanes pose an even greater threat to water quality, as floodwater surrounds or inundates barns full of animals and lagoons full of waste. When that happens, the earthen berms surrounding the hog lagoons may fail, spilling millions of gallons of raw sewage into the waterways, and those heavy rains can fill a lagoon until the combination of rainwater and hog waste spills over the top.

That’s exactly what happened during Hurricane Florence in 2018. In North Carolina, 46 hog waste lagoons were flooded and another 60 spilled over, and all of that waste ended up in the waterways.

Poultry CAFOs

In the past two decades, North Carolina’s poultry industry has exploded.

However, because the industry only reports to the North Carolina Department of Agriculture, there is no public record of how many of these facilities exist or even where they are.

North Carolina’s poultry industry is growing and largely unregulated, which makes it nearly impossible to understand the environmental impact it’s having on our waterways and communities.

Riverkeepers’ only way to determine the number and location of poultry facilities is to cobble together information from limited statements given by state agencies, what’s in the news, and by actually flying over facilities and scouting them out themselves.

Like swine CAFOs, poultry CAFOs produce a lot of waste every year. The method of disposing of poultry waste is to remove the dry litter from the confinement buildings, where it is stored outdoors in large piles before being used locally as fertilizer on pastures and hayfields or shipped out of the area for use as fertilizer elsewhere.

It is when the dry litter — a mix of poultry waste, spilled feed, feathers and material used as bedding — is stored outdoors, particularly if left uncovered, that it poses a threat to water quality.

A good rain on an average day can readily wash dry litter into nearby ditches, streams, creeks and rivers. During a hurricane, it’s much worse. For example, in 2018, 35 poultry facilities in eastern North Carolina were flooded during Hurricane Florence; more than 3.4 million poultry were killed, according to the poultry industry. Considering that each facility holds tens of thousands of birds, that’s an enormous amount of waste poisoning local waterways and aquatic life.

Latest News

Sound Rivers investigates Swift Creek hog waste spill

May 2nd 2024

Flight an education on coal ash cleanup

March 14th 2024

Riverkeeper win: White Oak must close existing hog-waste lagoons

December 14th 2023

ACTION ALERT: NCDEQ permits need OUR input!

October 26th 2023

Riverkeeper introduced to aerial investigation

October 26th 2023

Aerial tour reveals major Neuse pollution threats

October 5th 2023

People’s Hearing sets community organizing example

September 21st 2023

Nahunta Swamp pollution investigation continues

July 27th 2023

State finds hog facility is polluting waterways

July 20th 2023

Watersheds

March 28, 2023

Watersheds

Tar-Pamlico River Basin

The Tar River begins as a freshwater stream in the Piedmont near Roxboro, flowing east to become the Pamlico River near Washington, then draining into the Pamlico Sound before meeting the Atlantic Ocean. Major tributaries in the upper basin include Swift, Fishing and Tranters creeks and Cokey Swamp, as well as the Pungo River in the lower basin. It also includes Lake Mattamuskeet, home to Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge and, at more than 18 miles long and six miles wide, is the largest natural lake in the state.

The Tar-Pamlico River Basin is made up mostly of wetlands and forested areas covering about 55% of its area, with about one-quarter made up of agricultural land and a small portion of urban, developed areas. This basin is rural when compared to the Neuse, which is similar in size and hydrology.

A gateway to the coast, the Tar-Pamlico feeds into a highly productive estuary that is a nursery for more than 90% of all the commercial seafood and recreational fish caught in North Carolina. The Albemarle and Pamlico sounds comprise the second-largest estuary system in the United States.

Sadly, the Pamlico River has been plagued with environmental problems. Excessive growth of algae and increasing numbers of diseased and dying fish over the past two decades suggest a decline in water quality. Municipal treatment plants that discharge wastewater into rivers and streams and runoff from nonpoint sources, such as farmland, timber operations and urban areas, also contribute pollution. These sources increase levels of the nutrients in the watershed — primarily nitrogen and phosphorus – resulting in an unbalanced ecosystem.

Neuse River Basin

The longest river in North Carolina, the Neuse River stretches 248 miles from the Falls Lake Reservoir Dam in the Piedmont to its mouth at the Pamlico Sound and the state’s first capital of New Bern. At its mouth, six miles across, it’s the widest river in U.S. and part of our nation’s second-largest estuary. Major tributaries include Crabtree, Swift and Contentnea creeks and the Eno, Little and Trent rivers. The Neuse River Basin is a critically important body of water for nearly one-sixth of the state’s population.

Among the biggest threats to water quality in the lower Neuse River are large quantities of nutrient pollution, especially nitrogen and phosphorus.

Nutrient pollution is a form of water pollution, in which water is contaminated by excessive inputs of nutrients.

This type of pollution results from: runoff from large fertilized areas (such as golf courses), urban developed areas and farm fields treated with fertilizer, pesticides and herbicides; animal waste washed from lawns; and industrial meat production facilities discharging into our rivers and streams. Swine concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), for example, contribute 60% of the excess nitrogen and phosphorus.

Some nutrients can be beneficial to aquatic life in small amounts, but large amounts can cause excessive plant growth, algal blooms and low levels of dissolved oxygen in the water.

To a lesser degree, water quality in the Neuse River Basin is being affected by pollution from more than 400 industrial and municipal sites that are allowed by state permit to discharge treated wastewater into streams and rivers. Both of the above situations can be harmful to fish and other aquatic life.

Latest News

Riverkeepers eye pollution sources from the sky

May 9th 2024

Riverkeepers, ED attend NC Conservation Network Conference

May 9th 2024

Sound Rivers staff meets up for campus stormwater tour

May 9th 2024

Wetlands a hot topic at Brewery 99 meetup

May 9th 2024

Open house a forum for Jack’s Creek concerns

May 9th 2024

Sound Rivers investigates Swift Creek hog waste spill

May 2nd 2024

Riverkeeper, association partner for Ellerbe Creek monitoring

May 2nd 2024

Adkin Branch relieved of 70 lbs of trash

May 2nd 2024