Tag: Tar River

40 Stories, 40 Years: Jim and Sherrie Starr

March 20, 2023

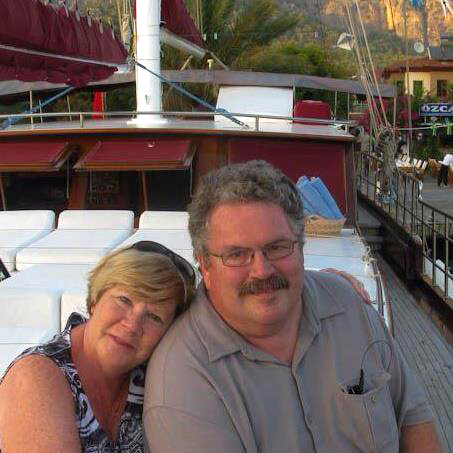

JIM AND SHERRIE STARR, NEW BERN

“We really tried to give the education piece of it equal billing. We were going for environmental awareness. We were really trying to understand when there were issues with the rivers and what they were.”

Jim and Sherrie Starr were drawn to New Bern by the prospect of sailing those wide, open waters. That was in 2005, but retirement didn’t last long after the couple became acquainted with neighbor — and then-Neuse Riverkeeper Foundation board president — Dave McCracken.

“He recruited me first to be a volunteer and then Sherrie got heavily involved with fundraising,” Jim said. “When I started as a volunteer, it was specifically to try to create a volunteer program that ended up being called ‘River Watch.’ That was all about getting members educated about what to look for when they were out on the river, for follow-up by the Riverkeepers or the state agencies to enforce environmental law.”

As Jim became more involved as a volunteer, then as a member of the NRF board, Sherrie leant her fundraising expertise to NRF’s cause.

“I had been involved in Denver in a lot of fundraising activities, so I volunteered,” she said.

In 2009, she joined the committee for Taste of Carolinas, at that time five years old and floundering.

“At that point, it was failing,” Sherrie said. “I thought, ‘This is a lot of work for $4,000, maybe we should do it differently.’”

The committee set about “tweaking” Taste, adding the chef’s competition, and the resulting reinvention of the signature NRF event was a success — almost too much of a success, according to Sherrie.

“In 2011, we had too many people. We were a victim of our own success,” she laughed.

More tweaking ensued, including making it a patrons-only event, which kept the numbers up to fundraising expectations, but down enough there were no lines and plenty of food.

“It was fun. It really was a fun group of people we were working with. It was so important for the organization, because it became our primary external fundraiser other than membership.

I was especially interested in the children’s education piece and being able to pay for that,” Sherrie said.

The education aspect was equally important to Jim.

“We really tried to give the education piece of it equal billing. We were going for environmental awareness. We were really trying to understand when there were issues with the rivers and what they were,” Jim said.

Under Jim’s watch as board president, NRF initiated education sessions where Riverkeepers did an overview of environmental law; NRF set up a mechanism for the public to report issues on or in the waterways; and a daylong symposium about fracking was organized at the North Carolina History Center at Tryon Palace.

“We had a whole discussion of the risks of fracking. That, I think, was another part of the public awareness piece that took a lot of work, and we had some controversy. We had pro-fracking and anti-fracking speakers and really tried to have a balanced view,” Jim said. “We advertised it, got it on NPR, and we got people who were concerned about the river, and we got people who thought all this stuff was a bunch of hooey, who wanted to hear what the issue was.”

Jim initially had reservations about the merger between Neuse Riverkeeper Foundation and Pamlico-Tar River Foundation, but by the time his presidency ended, two of oldest conservation organizations were poised to become Sound Rivers — “a very good thing,” he said.

The issues facing the rivers then are the same one facing the rivers today, Jim said: nutrient pollution, particularly caused by concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) and stormwater runoff; fish kills due to algal blooms caused by both. He said his wish is that environmental law would be enforced to the point that Sound Rivers can focus solely on educating people about and advocating for the rivers.

“I used to say in the NRF, the NRF’s ultimate goal is not be in business,” Jim said.

40 Stories, 40 Years: Jerry Eatman

March 20, 2023

JERRY EATMAN, RALEIGH

“I grew up hunting fishing, with a love for the outdoors. We used to travel to the Pamlico and Pungo, and I would come down there with my dad. Then when I was in college I came down with my friends. It’s an area that has been near and dear to my heart for many years.”

Also near and dear to Jerry Eatman’s heart was conservation — the Raleigh business attorney’s work often overlapped with land-use issues, and he’d been involved with conservation groups for years. When he and his wife built a second home on the Pamlico River, Eatman went looking for an organization that shared his interests, particularly about water quality and wetland preservation.

“I was really looking for something grassroots, hands-on, doing the dirty work of conservation, and I found it in PTRF. That’s exactly what I was looking for,” Eatman said. “The thing I’ll say about Sound Rivers and PTRF — and I’ve said this many times — you get the biggest bang for your dollar. I’ve never worked with so many people who do so much with so little. They all have just been tremendous; they’ve done a great job. The people I’ve been on the board with over the years — they give their time, they actually roll up their sleeves and clean up the river and lobby legislators, and that’s always a thankless task.”

Eatman’s volunteerism, however, has extended beyond that, delving into the law by lending his legal expertise to the Sound Rivers’ cause, also serving as board president before and during the merger between the Neuse Riverkeeper Foundation and the Pamlico-Tar River Foundation to become Sound Rivers in 2015.

“There are very few options for pro bono environmental help. There’s, of course, SELC, and they’ve done some wonderful work, but they have way more demand for assistance than they have the capacity to handle. They only have so much bandwidth. They knew I was willing to take things on if it was important,” Eatman said.

He’s been a part of several legal successes over the years, cases in which he said Sound Rivers has made a difference: at Rose Acre Farms, preventing another poultry farm from building in the Tar-Pamlico watershed near Rocky Mount, legally challenging a DEQ permit that would allow the discharge of millions of gallons of fresh water per day into the brackish headwaters Blounts Creek and most recently, stopping the clearcutting of land for a proposed landfill that would neighbor a historically Black neighborhood in Kittrell.

“It’s hard to say sometimes how much you’re moving the needle, but I do feel like that we made a difference,” Eatman said. “One of the things I’ve seen in the last 10 years, with big funders of environmental efforts, is that more and more people have come to look at it as an investment. Many of these people are asking, ‘What am I getting in return for my investment? Show me some results.’ And that’s hard to do, because sometimes you’re accomplishing really bad things from happening. It’s not so much what you did — it’s what you kept from happening. Did we stop something in its tracks? Did we stop some bad legislation? Did we stall enough that they gave up and left? Your wins are not as obvious as in other areas.”

What he’s also seen is Sound Rivers evolve into one of the most respected environmental voices in North Carolina.

“I was there when we made the transtion from kind of a local, sort of river cleanup group, to an organization that represents one of the largest estuarine systems in the world,” Eatman said. “It is the voice of that system. Thanks to people like Heather (Deck) and a long line of really good executive directors, we’ve got a lot of credit in the environmental community. … The respect that state organizations have for our organization speaks volumes about the integrity of the organization — it’s a wonderful organization. I can’t say enough about it.”

40 Stories, 40 Years: Charlie Adams

March 20, 2023

CHARLIE ADAMS, GREENVILLE

“We were activists. We were rabblerousers, and we didn’t give a damn. A lot of people didn’t like us. That was then, and we managed to get away with it without being shot. And we’re still here.”

Charlie Adams laughs when he talks about how the founders of the Pamlico-Tar River Foundation were perceived by the general public back in 1981. Their ideas weren’t popular, even though most people paying attention could see the issues facing the Pamlico River.

“At that time, we thought it was sedimentation, and just ignorance, particularly non-point source pollution and point-source pollution — that was awful back then,” Adams said. “Of course, the Texasgulf people wanted a new mine permit and, boy, did we put them through their paces. Initially, it was kind of something that we just felt we had to do. Texasgulf was going to take the freshwater under the ground and turn our river into something it wasn’t. And we fought them tooth and nail.”

It was one of the issues that galvanized river-lovers, gathering a community of likeminded people together to start a grassroots movement on the banks of the Pamlico. Ultimately, PTRF would be a major factor in major modifications to the Texasgulf operation, including a tremendous reduction in the discharge of process wastewater into the river, and the implementation of the company’s wastewater recycling system.

What brought them together was their passion for the river.

“Honest to God, we never had a meeting that lasted less than two hours,” Adams laughed. “Somebody said ‘Let’s have an oyster roast,’ so we did; somebody said, ‘Let’s do a newsletter,’ so we did; somebody said, ‘Do a slideshow of all the problems with the river,’ so we did. I am proud that, most of all, that we did all that.”

It was brainstorming how to make the public aware of PTRF’s mission that prompted the first PTRF Oyster Roast.

“Everybody likes oysters, but people rarely think of where they come from,” Adams said. “When we cranked up the Oyster Roast in 1986 or ’87, I think that was the key to getting us off the ground.”

The Oyster Roast became a major fundraiser for PTRF and remains one today for Sound Rivers, in addition to being a signature annual event for the City of Washington.

And it was brainstorming how to educate current and future generations about local waterways and the threats they face that prompted PTRF founders and members to plant the seed for an estuarine resource center. The PTRF board, at the time, asked for, and received funding, through the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership for a feasibility study for a one-of-a-kind museum.

“We managed to snooker away a few dollars for a proposal to do the Estuarium. Anyway, long story, short — we did the Estuarium,” Adams laughed.

But some people’s perception of PTRF as “rabblerousers” deterred other, much-needed supporters from signing on with the project, according to Adams.

“There was a resistance, and when we finally had the Chamber of Commerce on board, if we had to take a back seat, then that’s what we did,” Adams said.

Passion for the Pamlico, education about the importance of its health and a lot of good intentions were the foundations of the organization that has become a powerful and respected advocate for waterways covering nearly 24% of the state of North Carolina.

“We tried to put together a group of people who represented the whole ball of wax that goes into the why you love the river — it ain’t about a bunch of white people with houses on the riverside. It’s also about the people having sufficient fishing up in Chicod Creek,” Adams said.

Adams own Pamlico roots go back to the river cottage his grandfather built on Broad Creek in 1954. He has no recollection of when he met the boys who would later become the founders of PTRF in 1981, but they all met on the river — fishing, swimming, boating, skiing through the summers — and he was a natural fit for the cause. He still is today.

“Swimming, fishing, all those things that drew me to it, a gorgeous May afternoon on my boat, I wouldn’t give it up for nothing,” Adams said. “Thank the Lord, somebody heard us.”

40 Stories, 40 years: Harrison Marks

March 20, 2023

HARRISON MARKS, WINSTON-SALEM

When Harrison Marks applied for the job as executive director of the Pamlico-Tar River Foundation, he was returning to his environmental roots. At Dartmouth College, he’d done environmental research on heavy metals and was heavily involved in the Dartmouth Outing Club, the oldest and largest collegiate club in the country, emphasizing outdoor recreation and environmental stewardship.

What followed college, however, was a career in banking.

“I spent my whole working career, until 2005, in banking institutions. I took an early retirement, I took a couple of years off, but I went back to work after the 2008 economic meltdown, until 2013. Then we moved back to New Bern, and I thought, ‘I’m too young to not do anything,’” he laughed.

Marks believes it was the sales pitch in his cover letter that got him an interview, but it was the combination of his passion for the environment and his background in business that got him hired.

“It was challenging. (Now Executive Director Heather Deck) certainly had all the environmental knowledge that the organization needed,” Marks said. “And I liked the challenge. I liked working on something that really mattered to me.”

When Marks came aboard in 2013, the battle to keep a limestone mining company from discharging up to 10 million gallons of fresh water per day into the brackish headwaters of Blounts Creek was ramping up.

“The first thing that I went to was a public hearing that was at the community college — I don’t even know that I’d been hired yet, but that’s was what was going on then, and I guess it’s still going on,” he said.

He found that in the nonprofit world, especially that of an environmental nonprofit, things were a bit different on the non-corporate side.

“Having come from a company — which I felt like for most of my career was pretty highly ethical — I was surprised that some companies were not open to discussion or reasonableness, and it was often necessary to litigate. I thought it would be possible to come up with reasonable solutions, but I found out really quickly that they weren’t interested in doing anything about the pollution they were creating. I thought, ‘Surely they would see reason,’” he said. “But I think the biggest surprise was how difficult it was to raise money. We’ve been fortunate with grants. Coming from a large organization like Wachovia, spending $5,000 wasn’t something you really thought about. But spending $500 at an environmental nonprofit is something you really have think about. Every gift matters. We know that Americans give a lot of money to charities, but to environmental nonprofits, it’s considerably less. It’s a little less tangible — the work of environmental organizations like Sound Rivers do — but it’s vitally important.”

Though at the helm of Sound Rivers for a short four years, Marks’ mark on the organization is significant: it was he who pushed the idea of PTRF joining forces with the Neuse River Foundation to form Sound Rivers, then oversaw the merger of two of North Carolina’s oldest grassroots conservation organizations.

“I talked about it with (then-PTRF Board President) Jerry Eatman, then met with Jim Kellenberger, who was the president of Neuse River Foundation,” Marks said. “I went to Oriental to meet Jim, and Jim, initially, wasn’t particularly interested.”

That changed during their meeting, when Marks pulled out a map of eastern North Carolina’s waterways.

“As we looked at the map together, Jim realized what it meant and what the organization could be, and he got on board. Then it was a matter of convincing both boards,” Marks laughed.

There were committee meetings held on neutral ground in Goldsboro and public meetings held with PTRF and NRF membership. Marks’ career in banking, overseeing several mergers, meant he was the ideal person to the lead the merger of PTRF and NRF to become a powerful advocate for waterways covering nearly a quarter of the state.

That Sound Rivers is thriving after 40 years, Marks credits Sound Rivers’ supporters, as well as the leadership of Deck after his retirement in 2017.

“It was clear to me that Heather was the right person for executive director. She worried about all the things an executive director does, so I told her ‘You may as well be executive director,’” he laughed. “Forty years is really impressive, and I think it’s a credit to the people of New Bern and Washington. I think the people who got it started, people like Dick Leach and Grace (Evans) and others that were there at the beginning — the fact that they saw the need, started it and kept it going for 40 years — and 40 years later, they’re still a voice for the river.”

After retiring, Harrison and his wife, Suzie, spent two years on their 38-foot Cabo Rico, sailing as far north as Maine and as far south as the Bahamas, before landing permanently in Winston-Salem.

40 Stories, 40 Years: Meredith and Mira Loughlin

March 20, 2023

MEREDITH AND MIRA LOUGHLIN, WASHINGTON

When Meredith and Neil Loughlin moved to Washington in 2009, they were looking for a slower pace and to make an investment in their future — theirs and downtown’s.

“Neil and I have always been drawn to the water. Neither one of grew up having a boat, but we find being on the water so peaceful, which is why we moved from Greensboro to Raleigh, then back toward the coast. I guess we were working our way back East,” Meredith said.

More than a decade later, their business, Lone Leaf Gallery and Custom Framing, is thriving; their family has grown by one with the addition of daughter Mira; and their passion for enjoying and protecting the waterways is now being passed down to the next generation.

The Loughlins’ involvement with Sound Rivers started with one of its signature events — the annual Oyster Roast — and a donation from Lone Leaf for the silent auction, usually oyster knives, crafted from railroad ties and made locally. As their familiarity with Sound Rivers grew, so did their appreciation for the work it does.

“I guess I started to realize just how important it was to have a Riverkeeper and someone whose primary focus is the health of the water,” Meredith said. “If Sound Rivers isn’t there doing that, whose job is it? I really love everything they do, from the stormwater mitigation to monitoring where pollution comes from. River basins are so complex, and the water comes from just everywhere. They use the data to inform the public of what effects our rivers, but also make rules for building practices and industry. They do so much to gather information so we can make wise decisions in our planning and in our developing.”

The Loughlins are now putting the science of Sound Rivers into personal practice. For the past two summers, Meredith and 8-year-old Mira have volunteered for Sound Rivers’ Swim Guide, collecting water samples for testing, the results of which are shared to let the public know where it’s safe to swim. This year, mother and daughter will be sampling for microplastics, helping with a two-year-long, statewide program in which Sound Rivers and 15 other Riverkeepers are taking part, and now, a new lesson in Mira’s education.

The Loughlins are now putting the science of Sound Rivers into personal practice. For the past two summers, Meredith and 8-year-old Mira have volunteered for Sound Rivers’ Swim Guide, collecting water samples for testing, the results of which are shared to let the public know where it’s safe to swim. This year, mother and daughter will be sampling for microplastics, helping with a two-year-long, statewide program in which Sound Rivers and 15 other Riverkeepers are taking part, and now, a new lesson in Mira’s education.

“Microplastics sampling — I thought it was really cool, because it’s like hands-on, citizen science. It shows her how to gather data in the field; how scientists gather data to form a bigger picture,” Meredith said. “I want to her see how it plays out in her local community. Science is really cool, but it always seems like it’s farfetched unless you see it applied in your community. … It’s great for her, just meeting the people who have these jobs like (Pamlico-Tar Riverkeeper Jill Howell) and the interns. She can see people who do this for a living, and maybe when she’s thinking about what she was wants to do for her career, she can think back to the people she’s met at Sound Rivers.”

The Loughlins, as a family, are dedicated to promoting sustainability and protecting the waterways in all aspects of their lives.

“Whether I know I’m doing it or not, it’s just what we gravitate toward,” Meredith said. “It’s almost like a hobby: where art is my job, science and sustainability are my hobby.”

40 Stories, 40 years: Rick Dove

March 20, 2023

RICK DOVE, NEW BERN

“As a kid, I always wanted to be fisherman, but my mother and father talked me out of it,” said Rick Dove.

Dove got his chance, however, after earning a law degree, then getting a draft notice for Vietnam that resulted in a 20-plus-year career in the U.S. Marine Corps.

“I came here in 1975; the Marine Corps brought me here. When I walked out the gate for the last time, I traded my spit-shined shoes and put on the dirtiest clothes I could find and became a commercial fisherman,” Dove said. “Things were great until about 1990.”

That’s when the catch from the Neuse became riddled with sores; Dove and his son, Todd, who fished with him, had them too.

“I wouldn’t eat the fish, so I decided couldn’t sell them either,” Dove said.

Dove hung up his dirtiest clothes, went back to practicing law and found a new calling when he was hired as the Neuse Riverkeeper at the behest of early Neuse River Foundation board member Grace Evans. At that point, NRF had been successful in its bid for a statewide ban on cleaning products containing phosphorous, which entered the waterways through sewage treatment plants, much to the detriment of aquatic life, but NRF wanted to do more.

When Dove came aboard, he put his law degree to use again, this time going after those polluting the river, directly.

“We sued wastewater treatment plants and hog farms. Our docket had 20 cases on it, all the time. We were in court a good bit of the time, but most of our cases were settled out of court,” Dove said.

Neuse River Foundation grew from 70 members to more than 2,000. The Neuse River had gotten a bad reputation, devastating both tourism and the housing market, and disparate interests banded together to do something about it. Hundreds of volunteers patrolled and sampled the waters at stations from the lower Neuse up to Raleigh, and local pilots volunteered their planes to get a bird’s-eye view of pollution sources. A designated force of creek-keepers took an active role in tracking salinity, turbidity and oxygen levels in tributaries.

“It was a very active time in the ’90s. We got pretty good results with all the screaming and yelling we were doing about the health of the river,” Dove said.

Results included injunctions against industrial hog farms and EPA payouts to clean up rivers, as well as the creation of pollution-reducing rules by the state that were put in place for the Neuse River Basin in 1997.

But deep budgets cuts to North Carolina’s Department of Environmental Quality over the years, has meant watching over the waterways and doing much of the work necessary to keep rivers swimmable, fishable and drinkable has fallen to organizations such as Sound Rivers.

“If it’s going to get fixed, it’s going to be fixed by the waterkeepers. There’s nobody else out there doing the work. The rivers are screaming because they’re out of balance with nutrients, and when nature goes out of balance, it comes back with things like fish kills,” Dove said, referring to a month-long fish kill on the Neuse this fall that brought public concern to a level not seen in years. “I’d like to see us get back to what we used to do. We need to get tough again. Somehow, we need to get the message out to the public forum. We don’t have to be all negative, but we certainly have to speak for the river in ways that are honest or strong. You can’t compromise the river to support pollution. You just can’t.”

40 Stories, 40 Years: April Turner

March 20, 2023

APRIL TURNER, CHAPEL HILL

April Turner is a University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill junior on a path to a medical degree. But the summer between her freshman and sophomore year, she became an environmentalist.

Courtesy of a Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation grant, the Greensboro native teamed up with Sound Rivers as an intern and got an introduction to the environment.

“It was an internship that piqued my interest, because when we think about health, we often neglect to think about the role the environment plays in health. I wanted to explore more of that connection of humans and the environment and vice versa,” April said.

That exploration came in variety of ways, from managing the Washington and New Bern offices to getting out in the field, taking water samples and testing for bacteria.

“What didn’t I learn?” April laughed. “For starters, I got to learn more about the environment and how we interact with the environment. I’d never really thought about, if there is fecal bacteria in the water, you don’t you have to ingest it; dermal interaction is enough (to affect health) … I learned to work with volunteers and read samples. I learned how to connect and engage with the community, for sure — especially with Swim Guide. I worked on translating everything to Spanish and increasing our outreach to the Spanish-speaking community.”

Of Colombian descent, April learned to speak Spanish as a child, but translating words associated with Sound Rivers’ work was a new experience.

“It’s something I want to use in my career, but prior to Sound Rivers, I never got to explore the language of environmental health,” she said.

A summer spent living in Greenville, working on the waterways of the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico river basins and taking advantage of opportunities to get out and interact with the natural world has had a lasting impact on the future doctor.

“The importance of the Sound Rivers is not only to improve the environment, but to teach the community about it. It’s made me much more conscientious: am I wasting water or using it efficiently? Am I doing what I can to clean up the waterways or the roads or am I adding to the problem? Sound Rivers tries to make people understand the ‘why’ of it, and when people understand the ‘why,’ that’s when they want to take part — that’s when they want to help protect this wonderful place we call home,” she said.

40 Stories, 40 Years: Bob Daw

March 20, 2023

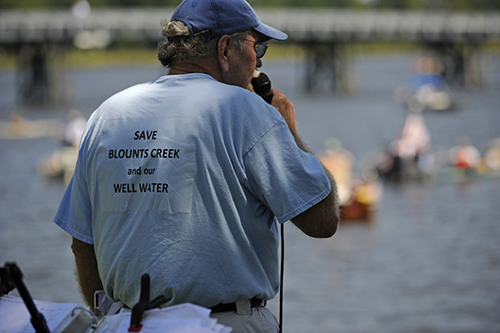

BOB DAW, BLOUNTS CREEK

Blounts Creek is home to Bob Daw. A Goldsboro native, Daw’s introduction to the creek came through his father. It had the best trout fishing, closest to home—much closer than the 120 miles they’d previously traveled to fish the Scuppernong River.

“Me and him spent a lot of good times down here fishing. If I weren’t working, if I got one night, I was down here in these cabins, fishing, playing guitars around the fire, getting to know these people here,” Daw said.

Daw spent his working life as a manufacturing manager for Cooper Standard, traveling all over the world, but Blounts Creek kept calling him back. He met his wife, Phyllis, there, and the couple had a particularly Blounts Creek wedding — they were actually married on a boat at the old Blounts Creek bridge, with a fleet of guests surrounding. And they were in the right place at the right time when property next to the old fishing camp cabins became available. It’s now their dream retirement home.

In 2011, when the first rumblings that a mine would be built in neighboring Vanceboro, and its millions of gallons of wastewater a day would potentially be dumped into the headwaters of the creek, Daw knew it had to be stopped.

He had history with Martin Marietta Mining.

“Fifty years ago, we would always go to Bachelor’s Creek to catch the big brim. But over the years — we didn’t know why — but you couldn’t catch nothing. The creek was so quiet, you couldn’t even find a snake there,” Daw said. “Then we found out about the mining. We didn’t know the name, we just heard that there was a big mining company, dumping all their wastewater in the creek. When I found out it was the same bunch, and knowing just how much it could damage the recreation and the fishing and the fun of people coming from all over to Blounts Creek, I was mad right out the gate — I said, ‘Let’s go get ‘em, let’s fight, let’s go.’”

Daw and a core group of Blounts Creek residents — including Cotton Patch Landing owner Jimmy Daniels, tour-boat Capt. Bob Boulden and retired schools’ superintendent Ed Rhine—launched “Save Blounts Creek” which became an advocacy and fundraising arm of Sound Rivers’ legal battle not to stop the 640-acre limestone pit mine from being built, but to find a better way to dispose of all the fresh water used in the mining process. Experts knew that much fresh water would irreparably harm the creek’s existing aquatic life, and there had to be a better way.

“I’ve always been passionate about Blounts Creek. I don’t remember if I’d already signed up or joined Sound Rivers before the ‘Save Blounts Creek’ campaign, but the awareness for me was that Sound Rivers was leading the charge to block Martin Marietta off and take them to court,” Daw said. “I’m sure that there was a lot of new memberships encouraged by the battle, and I’ve always tried to help out with things. I don’t have deep pockets, but Linda (Boyer) and I will play music for events, and just try to pass the word to donate. We raised a lot of money for that legal battle.”

Nearly a decade later, the case is still winding its way through the courts. There have been wins; there have been losses. Blounts Creek’s fate will be decided by the North Carolina Supreme Court, likely this year.

Daw remains passionate saving Blounts Creek — the source of many sunset cruises on his pontoon boat and fried fish dinners, where friends and family gather ‘round and evenings end with music played under the stars.

“I’ve got five granddaughters and three great-grandsons. They love Blounts Creek, they love to come down here. We’ve got four active eagles’ nests. We go around every year, and we count our osprey nests,” Daw said. “Saving Blounts Creek is for the future and enjoyment of so many people. With the citizens — unless we do create some kind of a shockwave, marches or boat rallies — it’s our only way to stop it, with the lawyers and attorneys and the courts. That’s the only way to deal with these people and, of course, Sound Rivers provided that resource. That’s why we rallied around and raised money to support Sound Rivers … I’m all about protecting the waters and supporting Sound Rivers.”

40 Stories, 40 Years: Joe Hester

March 20, 2023

JOE HESTER, ROCKY MOUNT

“Most of our pJoe Hester doesn’t recall how he first became aware of the Pamlico-Tar River Foundation, now Sound Rivers. But the Rocky Mount attorney has been environmentalist for as long as he can remember.roblems for the river have always been, and now certainly are, from the land.”

“I was around for the first Earth Day, walking around the campus of UNC-Chapel Hill. I was around when they built the first nuclear facility in the state; I was there when they ditched and drained all the land in Dare County for farming,” Hester said.

Three decades later, he was at the helm of the Sound Rivers’ board when the decision was made to hire PTRF’s first riverkeeper, Heather Deck, now Sound Rivers’ executive director, though his involvement started long before — in the 1990s, when the river had reached a critical place.

“There was so much stuff going on that we were involved in,” Hester said. “PTRF was very involved; they coordinated, encouraged, mobilized state agencies to get Rocky Mount to upgrade its wastewater treatment plant — they had dumped 2 ½ billion gallons of raw sewage into the Tar (River), and it was terrible.”

Indeed, there were many things going on: PTRF was behind Swift and Sandy creeks being designated Outstanding Resource Waters, moving to protect “unique and special waters having exceptional water quality” and restricting types of development around them. Its members rallied around the “No OLF” movement, in which the U.S. Navy proposed building an outlying landing field in Beaufort and Washington counties that promised ecological devastation. PTRF had its hand in facilitating buy-outs of hog farms in the 100-year-flood plain after the historic flooding of Hurricane Floyd in 1999 and preventing a low-level radioactive waste dump from breaking ground in Edgecombe County, not to mention funding and grants to assist with the Albemarle-Pamlico Estuarine Study, Partnership for the Sounds, the North Carolina Estuarium — the only museum of its type in the world — the constructed wetlands on the Washington waterfront, and much more.

“The two people I think of when I think of PTRF are Dick Leach (a PTRF founder) and David McNaught (early executive director). We are where we are today, in my opinion, is because of them,” Hester said.

For his role in Rocky Mount city council ultimately nixing the construction by IBP of a hog-processing plant outside of Tarboro, Hester was given Sound Rivers’ Great Blue Heron award.

“We were involved; we went to hearings, but here’s why it was not approved: Sam Carlisle was my law partner, and he grew up in Tarboro. I found out that for IBP to exist, and to slaughter hogs 24 hours a day, seven days a week, it would have consumed 90- to 95-percent of all water designated for the growth of Rocky Mount. Sam knew everyone and went to talk to them, and that sank the IBP plan,” Hester said.

Hester said the role of PTRF then, and now of Sound Rivers, is to keep eyes on the ground, on the water — and on the data.

“One of the things I was also proud of was we came with facts. When we talked to a legislator, they knew we knew what we were talking about. We had the facts; we had the science. I was always proud that we were science-based,” he said. “It’s an organization that keeps its eyes out to protect the river. You have to be observant and cognizant of what’s going on in the watershed, and when you see what could be a deleterious effect — whether that’s an IBP or low-level radioactive waste dump — then you need to do the appropriate thing: provide the science to the decision-makers; mitigate; coordinate; when you can influence the rules, you try to do that. We’re for advocacy, we’re for education — yes — but we’re really for the watershed.”

Joe Hester and wife Betsy have been active Sound Rivers volunteers for more than 30 years, resulting in both the Hesters’ part-time residence in Washington, virtually next door to the site of Sound Rivers’ ever-popular Oyster Roast event, and Betsy now serving on the Sound Rivers board of directors.