Tag: land-use

Clean Water Act

March 21, 2023

Clean Water Act

Updates

The deadline for getting comments to EPA and the Army Corps urging that they halt plans to gut the Clean Water Act has passed, but things aren’t over yet. Stay tuned for more ways you can be involved soon!

NC Wrote Strong Comments to EPA Opposing Rollbacks: The North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality and Department of Justice sent excellent comments in to the federal agencies opposing the rollbacks.

Write a letter to the editor: Though the comment period is over, as EPA analyzes the comments received it is still important to show visible public support for clean water, one way to do this is to write a letter to the editor in your local paper. You can find some information on how to do that here.

EPA’s Waters of the United States Rule Aims to Gut Protections for Your Streams and Wetlands

Despite the fundamental necessity of clean water, politicians in Washington are trying to dismantle the Clean Water Act, which has kept our nation’s waters clean for nearly 50 years. This bedrock environmental safeguard is a central tool used by state and local governments to shield and protect clean water needed for healthy communities and families. Without it, polluted waters would threaten North Carolina’s local economies, communities, and way of life.

Allowing open dumping into upstream waters spells trouble for everyone downstream. Pollution dumped by industry flows from smaller streams into our rivers and lakes, across state lines and downriver, contaminating waters used by families and communities for drinking and recreation. The best way to protect clean water is to stop harmful pollution at its source, before it reaches our waterways.

Under the proposal by the administration and supported by industrial polluters, more than 49,000 miles of North Carolina’s streams and millions of acres of wetlands will again be at risk from pollution and destruction. At least fifty percent of North Carolinians get their drinking water from sources that rely on small streams that may lose critical Clean Water Act protections under the administration’s proposal. More than 7,000 miles of streams that feed into North Carolina’s drinking water sources would be at risk for pollution if the Clean Water Act is rolled back as the administration plans. Millions of acres of wetlands that provide flood protection, filter pollution, and provide essential wildlife habitat are at risk if the federal government moves forward with its plan.

Your voice will is critical to ensure North Carolina’s waterways are protected so please stay tuned on how you can help fight for our waterways.

More Information & Resources

Southern Environmental Law Center Fact Sheet

New York Times: Trump Rule Would Limit E.P.A.’s Control Over Water Pollution

The Intercept: EPA’s Own Data Refutes Justification for Clean Water Act Rollback

EPA fact sheet on major changes

North Carolina DEQ and DOJ comments regarding the rollback proposal

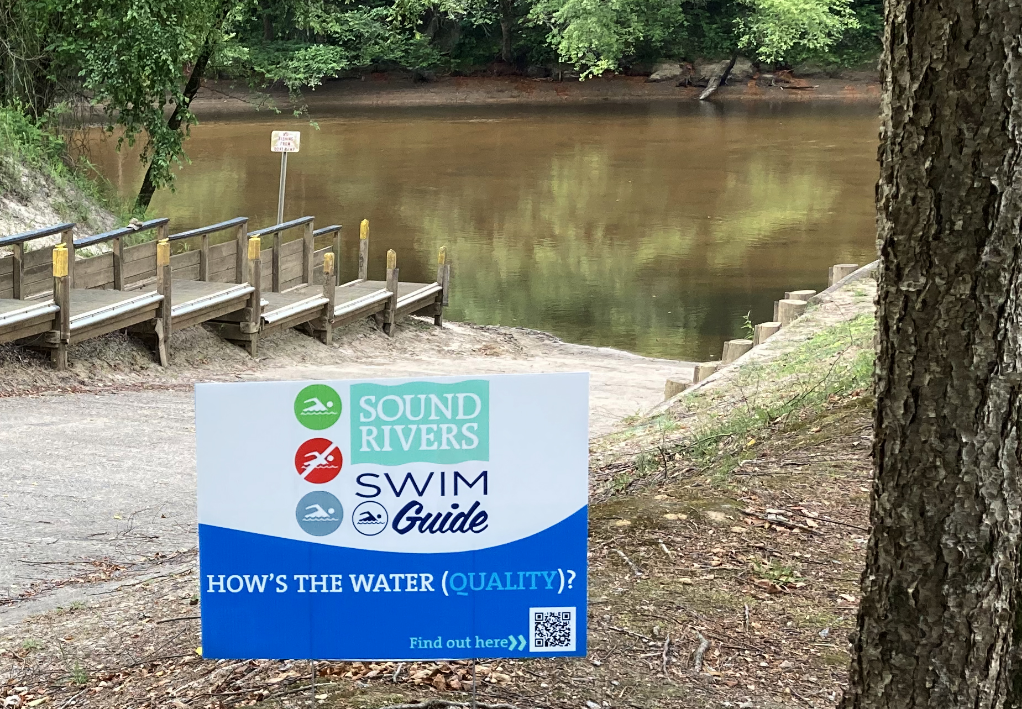

Adopt a Swim Guide Site

March 21, 2023

Adopt a Swim Guide Site

Click below to donate today!

El Programa de Swim Guide

March 21, 2023

El Programa de Swim Guide

Get your weekly water quality alerts here!

swim guide here

Want to get weekly water quality alerts straight to your phone? Text “SWIM” to 33222!

IN ENGLISH

Los encargados del río Neuse y Tar-Pamlico de Sound Rivers, trabajan con pasantes de verano y voluntarios para monitorear la calidad de agua en varios sitos en las cuencas de Neuse y Tar-Pamlico. Se toman muestras semanales en nuestros sitios, las cuales comenzamos desde finales de Mayo hasta el fin de Agosto. Monitoreamos nuestros sitios por la bacteria E. coli en las aguas dulces y por la bacteria enterococcus en el agua salada.

Tan pronto como estén disponibles los resultados de nuestro monitoreo, se publicarán aquí, en el sitio de web de Swim Guide, en la aplicación de smartphone, en nuestra página de Facebook, y se será anunciado por Public Radio East entre las 4 y las 6 de la tarde cada viernes. También, pueda recibir alertas de texto semanal durante el verano (envíe el mensaje NADAR a 33222 para formar parte de nuestra lista de alertas de texto).

RESULTADOS POR EL

el 29 de marzo 2024

Las pruebas semanales de Swim Guide finalizaron para el verano de 2023; sin embargo, ahora estamos probando sitios seleccionados mensualmente. Los sitios que se prueban mensualmente en Neuse incluyen Rolling View en Falls Lake; Buffaloe Road y Poole Road en Raleigh; Clayton River Walk; Busco Beach y la rampa para botes del río Neuse en Goldsboro; el acceso para botes y el área para nadar del Parque Estatal Cliffs of the Neuse en Seven Springs; la rampa para botes de la autopista N.C. Highway 11 en Kinston; Lawson Creek en New Bern; Slocum Creek en Havelock; y la rampa para botes de Midyette Street en Oriental. Los sitios en Tar-Pamlico son Stith-Talbert Park en Rocky Mount; Wildwood Park y Port Terminal en Greenville; y Havens Gardens y Pamlico Plantation en Washington.

El muestreo de Swim Guide se realizará el último jueves de cada mes y los resultados se publicarán en esta página al día siguiente.

EN EL RIO UPPER NEUSE

Buffaloe Road y Poole Road en Raleigh y el River Walk en Clayton no pasaron este mes.

EN EL RIO LOWER NEUSE

Midyette Street en Oriental no paso.

EN EL RIO TAR-PAMLICO

Havens Gardens en Washington y Port Terminal en Greenville no pasaron este mes.

Nuestra Misión

Monitorear y proteger las cuencas de los ríos Neuse y Tar-Pamlico que abarcan casi un cuarto de Carolina del Norte, y preservar la salud y belleza de la cuenca fluvial mediante justicia ambiental.

Criterios de Calidad del Agua

Los criterios de calidad de agua para la recreación de contacto usados por Sound Rivers vienen de Carolina del Norte y del EPA (Agencia de Protección Ambiental). Cuando la última muestra de un sitio presenta niveles de bacteria saludables, lo marcamos verde. Si la última muestra de un sitio no cumple con los criterios de calidad del agua, o presenta niveles de bacteria no saludables, lo marcamos con rojo. Cuando no hay información disponible o no hay resultados actuales, marcamos el sitio con gris.

E. coli, un tipo de bacteria que se encuentra en el intestino de personas y otros animales, es un buen indicador de contaminación fecal reciente. Aunque varios tipos de estas bacterias son inofensivas, algunos tipos nos pueden causar enfermedades, o causar problemas gastrointestinales más graves en grupos de personas más sensitivos.

El Programa de Calidad de Agua Recreativa de la División de Pesquerías Marinas, bajo el Departamento de Calidad Ambiental de Carolina del Norte, conduce pruebas adicionales en la región. Los resultados de estas pruebas son incorporados en los sitios listados en el sitio de web de Swim Guide y en la aplicación de teléfono celular.

Muchísimas gracias a nuestros patrocinadores, los cuales nos ayudan a traer

el programa Swim Guide para ustedes este verano!

Our History: Full Story

March 20, 2023

Our History: Full Story

VOICE FOR THE RIVER

It’s a clear, crisp November day in eastern North Carolina, and high above the lowlands surrounding the Trent and Neuse rivers, Samantha Krop is on a mission.

Through the window of a twin-propeller Cessna, Krop points out a massive, covered lagoon — part of a biogas-harnessing industrial swine facility — that ruptured and spilled millions of gallons of foam made from decomposing waste, dead hogs and expired deli meats over the land and into Nahunta Swamp in May of 2022.

“This facility has a clear history of illegally discharging waste, and DEQ knew it. They failed to take meaningful action to prevent a major pollution event from happening, and failed to adequately notify the public,” Krop says. “This is people’s drinking water; it’s the water they swim in; it’s the water they fish from — and the agency responsible for protecting it isn’t doing its job.”

Krop is the Neuse Riverkeeper, and she — like her counterpart on the Tar-Pamlico, Katey Zimmerman — regularly takes to the waterways and skies to surveil potential sources of water pollution. They’re the latest crew of Riverkeepers, carrying on a fight for clean water that’s been waged for decades. That battle began when two communities, separated by many miles of the Coastal Plain, took the health of the rivers in their own hands, forming grassroots organizations serving as watchdogs for the waterways. Today, they are Sound Rivers, a merger of two of the oldest environmental nonprofits in North Carolina, now celebrating more than four decades of being the voice for our rivers.

SOUND RIVERS

Forty years ago, a fundamental change had taken place in the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico rivers. Fish and crab, so abundant in previous decades, had declined. Forests of sea grass had disappeared, seemingly overnight.

“I grew up here, and I was born in ’48. I lived on the river, so I spent my childhood in the river. It was a blissfully ignorant time, an innocent time. We had no environmental concerns,” said Linda Boyer, who grew up at Summer Haven, just east of Washington. “Then, gradually, the area became more developed. We had a lot more houses on the river. We had a lot more serious, big farming. We had industry come in. Gradually the river became degraded because of all those factors, you know, slowly trickling down into the river. People started noticing fewer fish, fewer crabs; we started getting crab diseases. The future of the river — people started getting concerned about what would happen if there was no regulation.”

The change was not going unnoticed further south, on the Neuse.

“Back then, we swam; we didn’t get infections. We fished, we floundered, just really enjoyed it and didn’t think particularly of what the water might contain,” said Grace Evans, a lifelong sailor who first sailed the Neuse in 1960, then made the area her permanent home in 1972. “The first thing that we noticed back then was that there was a lot of trash, whether it was beer cans or just whatever people had thrown overboard — washing machines, toilets, hunters throwing deer carcasses in the creek. There was a lot of litter.”

But as massive fish kills began to occur regularly, clogging beaches and waterways with the dead and dying, a movement was started.

THE EARLY DAYS: ON THE PAMLICO

“It’s interesting to see the evolution of the organization, how we got from the kitchen table to the organization we have now. At the start, there was no staff, and I don’t know when or where we decided to call ourselves a board — that was a little presumptive on our part — but we just did what we needed to do to get things done,” laughed Dr. Ernie Larkin, one of the founders of Pamlico-Tar River Foundation.

PTRF, indeed, made its start around the kitchen table in the Summer Haven home of Ross and Linda Boyer.

“What were those early meetings like? Very long,” Boyer laughed. “We had two babies, and I would put the babies to bed, and I would sit in on the meetings. There was a lot to talk about, a lot to learn, a lot to try to come to grips with.”

Under the leadership of Dick Leach and Billy Jackson, seated at that table were long-time Summer Haven residents and other river-lovers determined to put a stop to the river’s decline. The first order of business was to sway Beaufort County commissioners from approving a plan to allow Texasgulf Chemicals Company to mine the riverbed at its Aurora site — and they did.

Throughout the remaining decade, Pamlico-Tar River Foundation led public resistance to many proposals that would have damaged the river, wetlands and more, and worked with Texasgulf, the state and other environmental agencies to resolve another ongoing issue at the Aurora facility: nutrient pollution. Nutrient may seem like an innocuous term, but when excessive nutrients are dumped into waterways, they feed algae, which leads to massive algal blooms and de-oxygenated water that kills fish in equally massive quantities.

“Some of it was just direct negotiation with (Texasgulf). I remember just going down there and talking to those folks and hearing what they had to say. And they did something; they changed their process with wastewater to recycle it,” Larkin said. “They were dealing with a lot of phosphates, a lot of nutrients, that they were putting in the water, and they knew that and did something about it.”

1989 was a turning point, however. It was the year the Tar-Pamlico River Basin was declared Nutrient Sensitive Waters by the Division of Environmental Management — those responsible for nutrient overloads needed to stop. It was also the year the Division of Marine Fisheries declared the river “commercially dead,” so decimated was the commercial fishing and crabbing industry.

On the Neuse, things were no better.

THE EARLY DAYS: ON THE NEUSE

“As a kid, I always wanted to be fisherman, but my mother and father talked me out of it,” said Rick Dove.

Dove got his chance, however, after earning a law degree, then getting a draft notice for Vietnam that resulted in a 20-plus-year career in the U.S. Marine Corps.

“I came here in 1975; the Marine Corps brought me here. When I walked out the gate for the last time, I traded my spit-shined shoes and put on the dirtiest clothes I could find and became a commercial fisherman,” Dove said. “Things were great until about 1990.”

That’s when the catch from the Neuse became riddled with sores; Dove and his son, Todd, who fished with him, had them too.

“I wouldn’t eat the fish, so I decided couldn’t sell them either,” Dove said.

Dove hung up his dirtiest clothes, went back to practicing law and found a new calling when he was hired as the Neuse Riverkeeper at the behest of Evans and other members of the Neuse River Foundation. At that point, NRF had been successful in its bid for a statewide ban on cleaning products containing phosphorous, which entered the waterways through sewage treatment plants, much to the detriment of aquatic life.

When Dove came aboard, he put his law degree to use again, this time going after those polluting the river, directly.

“We sued wastewater treatment plants and hog farms. Our docket had 20 cases on it, all the time. We were in court a good bit of the time, but most of our cases were settled out of court,” Dove said.

The Neuse River Foundation grew from 70 members to more than 2,000. The Neuse River had gotten a bad reputation, devastating both tourism and the housing market, and disparate interests banded together to do something about it. Hundreds of volunteers patrolled and sampled the water at points from the lower Neuse up to Raleigh, and local pilots volunteered their planes to get a bird’s-eye view of pollution sources.

A designated force of creek-keepers took an active role in tracking salinity, turbidity and oxygen levels in tributaries.

“It was a very active time in the ’90s. We got pretty good results with all the screaming and yelling we were doing about the health of the river,” Dove said.

Merging of Minds

Decades of advances in water quality were offset by steps backward, even as much-loved fundraisers to fund the work of the organizations drew large crowds of river-lovers — the PTRF Oyster Roast on the grounds of the Civic Center in Washington and NRF’s Taste of Coastal Carolina in New Bern. Then, in 2015, the voice for the river became louder when the Pamlico-Tar River Foundation and Neuse River Foundation merged to become a powerful advocate for protection of the watersheds covering nearly a quarter of the state of North Carolina.

“Sound Rivers has become a respected environmental voice,” Boyer said. “It’s always had integrity, and it’s always had one goal, which is to preserve the health of the river.”

Results included injunctions against industrial hog farms and EPA payouts to clean up rivers, as well as the creation of pollution-reducing rules by the state that were put in place for the Neuse River Basin in 1997. New rules for the Tar-Pamlico followed in 2000.

Heather Deck, Sound Rivers’ executive director, said that’s due to the long-time dedication of members, board members, volunteers and staff — too many to count.

“Over the past 40 years, we’ve been able to expand our efforts and influence to support many more communities up and down both rivers,” Deck said. “But the organization has remained true to its mission and effort to give the people a voice for the river and their communities. Everyone has a right to have an impactful voice in determining the protection and use of their communities’ natural resources — including our water resources — and no person should bear the disproportionate impact of pollution.”

But 40 years after two communities set the stage for grassroots environmental advocacy, gathering around kitchen tables and in borrowed offices, the work is far from over.

“People are just kind of shortsighted when it comes to the importance of a healthy environment, and it’s been so for a long time,” Larkin said.

Deep budgets cuts to North Carolina’s Department of Environmental Quality over the years has meant watching over the waterways and doing much of the work necessary to keep rivers swimmable, fishable and drinkable has fallen to organizations such as Sound Rivers.

“If it’s going to get fixed, it’s going to be fixed by the waterkeepers. There’s nobody else out there doing the work. The rivers are screaming because they’re out of balance with nutrients, and when nature goes out of balance, it comes back with things like fish kills,” Dove said, referring to the fish kills on the Neuse in recent years that have brought public concern a level reminiscent of the past. “I’d like to see us get back to what we used to do. We need to get tough again. Somehow, we need to get the message out to the public forum. We don’t have to be all negative, but we certainly have to speak for the river in ways that are honest and strong. You can’t compromise the river to support pollution. You just can’t.”

40 Stories, 40 years: Larry Baldwin

March 20, 2023

LARRY BALDWIN, NEW BERN

“I don’t have a job. I don’t have a career. I have a calling.”

Larry Baldwin went back to school fairly late in life to get a degree in environmental sciences. It was a chance meeting that took him straight to his calling — and to North Carolina and the waters of the Neuse.

The year was 2002, and the event was a panel discussion sponsored by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. Panelists included Delaware Riverkeeper Maya van Rossum and former Neuse Riverkeeper Rick Dove.

“I asked Rick, how would one get involved in this, and he said there happened to be a position available in North Carolina. A month later, I was packing up my house in Hagerstown, Maryland, and moving to New Bern,” Baldwin laughed.

For nine years, Baldwin monitored the lower Neuse River and its tributaries, responding to complaints about construction in new developments clear-cutting beyond the buffers required at the time and reports of fish kills, which happened far more that they should have, Baldwin said.

“It became pretty clear the main issue was CAFOs. I became involved in that fairly quickly, but it was the typical issues: wastewater treatment plants, stormwater runoff,” he said.

On the job, he found resilience and perseverance were key, especially when it came to funding.

“There were times when we were like, ‘Wow, how are going to make it to the end the year? Or even the end of the month?’ But that’s not just our environmental organizations; it’s any nonprofit,” Baldwin said.

Though he had moved on by the time the Neuse Riverkeeper Foundation joined with Pamlico-Tar River Foundation to form Sound Rivers, he said the merger was a benefit to both organizations.

“If you look across the state, there are number of organizations, but it gives us the opportunity to combine a lot of the efforts. You also increase your numbers, and — in the work we do — a lot of our success is based on us being able to mobilize and engage the members that we do have. There were some very real commonalities between the two organizations, but now you have a bigger pool of people, of members and volunteers, to draw on, who are now all a part of the same family,” Baldwin said.

Now the Crystal Coast Waterkeeper with Coastal Carolina Riverwatch, Baldwin said the work of waterkeepers everywhere has not changed much over his years as a Riverkeeper.

“It’s not getting any easier. You would think in this day and age that, by now, people in general would know we cannot treat our planet the way we have and not have bad results,” he said. “There’s more political influence on what is happening to our water quality, and it’s getting worse, not better. Water doesn’t belong to one party or the other, and it certainly doesn’t belong to industry. I see more industry — big industrial, big ag, big pharmaceutical — having more influence on our water, with little regard to consequences that happen as a result. … We cannot keep treating our water resources as a commodity that can be bought and sold.”

When Baldwin thinks of the future, he thinks about his 3-year-old grandson, and wonders what that future will hold for the next generations, especially when it comes to clean water.

“Basically, what you’re seeing is the bad stuff every day. Sometimes you go home at end of the day and say, ‘What did I accomplish?’ Not everybody can do this job, because you have to put this job in perspective, even when you don’t always know what the perspective is,” Baldwin said. “I guess the really frustrating thing about this is we’re not learning from our mistakes. It’s almost like we’re using our mistakes to make excuses for more mistakes.”

Baldwin says perseverance is what kept the NRF and PTRF going, both separate and together as Sound Rivers, and that same perseverance keeps many Waterkeepers doing work that is often intangible.

“It’s not just about what we’ve accomplished — it’s about what we’ve prevented from happening,” Baldwin said. “It’s the most frustrating job I’ve ever loved.”

40 Stories, 40 Years: Jim and Sherrie Starr

March 20, 2023

JIM AND SHERRIE STARR, NEW BERN

“We really tried to give the education piece of it equal billing. We were going for environmental awareness. We were really trying to understand when there were issues with the rivers and what they were.”

Jim and Sherrie Starr were drawn to New Bern by the prospect of sailing those wide, open waters. That was in 2005, but retirement didn’t last long after the couple became acquainted with neighbor — and then-Neuse Riverkeeper Foundation board president — Dave McCracken.

“He recruited me first to be a volunteer and then Sherrie got heavily involved with fundraising,” Jim said. “When I started as a volunteer, it was specifically to try to create a volunteer program that ended up being called ‘River Watch.’ That was all about getting members educated about what to look for when they were out on the river, for follow-up by the Riverkeepers or the state agencies to enforce environmental law.”

As Jim became more involved as a volunteer, then as a member of the NRF board, Sherrie leant her fundraising expertise to NRF’s cause.

“I had been involved in Denver in a lot of fundraising activities, so I volunteered,” she said.

In 2009, she joined the committee for Taste of Carolinas, at that time five years old and floundering.

“At that point, it was failing,” Sherrie said. “I thought, ‘This is a lot of work for $4,000, maybe we should do it differently.’”

The committee set about “tweaking” Taste, adding the chef’s competition, and the resulting reinvention of the signature NRF event was a success — almost too much of a success, according to Sherrie.

“In 2011, we had too many people. We were a victim of our own success,” she laughed.

More tweaking ensued, including making it a patrons-only event, which kept the numbers up to fundraising expectations, but down enough there were no lines and plenty of food.

“It was fun. It really was a fun group of people we were working with. It was so important for the organization, because it became our primary external fundraiser other than membership.

I was especially interested in the children’s education piece and being able to pay for that,” Sherrie said.

The education aspect was equally important to Jim.

“We really tried to give the education piece of it equal billing. We were going for environmental awareness. We were really trying to understand when there were issues with the rivers and what they were,” Jim said.

Under Jim’s watch as board president, NRF initiated education sessions where Riverkeepers did an overview of environmental law; NRF set up a mechanism for the public to report issues on or in the waterways; and a daylong symposium about fracking was organized at the North Carolina History Center at Tryon Palace.

“We had a whole discussion of the risks of fracking. That, I think, was another part of the public awareness piece that took a lot of work, and we had some controversy. We had pro-fracking and anti-fracking speakers and really tried to have a balanced view,” Jim said. “We advertised it, got it on NPR, and we got people who were concerned about the river, and we got people who thought all this stuff was a bunch of hooey, who wanted to hear what the issue was.”

Jim initially had reservations about the merger between Neuse Riverkeeper Foundation and Pamlico-Tar River Foundation, but by the time his presidency ended, two of oldest conservation organizations were poised to become Sound Rivers — “a very good thing,” he said.

The issues facing the rivers then are the same one facing the rivers today, Jim said: nutrient pollution, particularly caused by concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) and stormwater runoff; fish kills due to algal blooms caused by both. He said his wish is that environmental law would be enforced to the point that Sound Rivers can focus solely on educating people about and advocating for the rivers.

“I used to say in the NRF, the NRF’s ultimate goal is not be in business,” Jim said.

40 Stories, 40 Years: Jerry Eatman

March 20, 2023

JERRY EATMAN, RALEIGH

“I grew up hunting fishing, with a love for the outdoors. We used to travel to the Pamlico and Pungo, and I would come down there with my dad. Then when I was in college I came down with my friends. It’s an area that has been near and dear to my heart for many years.”

Also near and dear to Jerry Eatman’s heart was conservation — the Raleigh business attorney’s work often overlapped with land-use issues, and he’d been involved with conservation groups for years. When he and his wife built a second home on the Pamlico River, Eatman went looking for an organization that shared his interests, particularly about water quality and wetland preservation.

“I was really looking for something grassroots, hands-on, doing the dirty work of conservation, and I found it in PTRF. That’s exactly what I was looking for,” Eatman said. “The thing I’ll say about Sound Rivers and PTRF — and I’ve said this many times — you get the biggest bang for your dollar. I’ve never worked with so many people who do so much with so little. They all have just been tremendous; they’ve done a great job. The people I’ve been on the board with over the years — they give their time, they actually roll up their sleeves and clean up the river and lobby legislators, and that’s always a thankless task.”

Eatman’s volunteerism, however, has extended beyond that, delving into the law by lending his legal expertise to the Sound Rivers’ cause, also serving as board president before and during the merger between the Neuse Riverkeeper Foundation and the Pamlico-Tar River Foundation to become Sound Rivers in 2015.

“There are very few options for pro bono environmental help. There’s, of course, SELC, and they’ve done some wonderful work, but they have way more demand for assistance than they have the capacity to handle. They only have so much bandwidth. They knew I was willing to take things on if it was important,” Eatman said.

He’s been a part of several legal successes over the years, cases in which he said Sound Rivers has made a difference: at Rose Acre Farms, preventing another poultry farm from building in the Tar-Pamlico watershed near Rocky Mount, legally challenging a DEQ permit that would allow the discharge of millions of gallons of fresh water per day into the brackish headwaters Blounts Creek and most recently, stopping the clearcutting of land for a proposed landfill that would neighbor a historically Black neighborhood in Kittrell.

“It’s hard to say sometimes how much you’re moving the needle, but I do feel like that we made a difference,” Eatman said. “One of the things I’ve seen in the last 10 years, with big funders of environmental efforts, is that more and more people have come to look at it as an investment. Many of these people are asking, ‘What am I getting in return for my investment? Show me some results.’ And that’s hard to do, because sometimes you’re accomplishing really bad things from happening. It’s not so much what you did — it’s what you kept from happening. Did we stop something in its tracks? Did we stop some bad legislation? Did we stall enough that they gave up and left? Your wins are not as obvious as in other areas.”

What he’s also seen is Sound Rivers evolve into one of the most respected environmental voices in North Carolina.

“I was there when we made the transtion from kind of a local, sort of river cleanup group, to an organization that represents one of the largest estuarine systems in the world,” Eatman said. “It is the voice of that system. Thanks to people like Heather (Deck) and a long line of really good executive directors, we’ve got a lot of credit in the environmental community. … The respect that state organizations have for our organization speaks volumes about the integrity of the organization — it’s a wonderful organization. I can’t say enough about it.”

40 Stories, 40 Years: Charlie Adams

March 20, 2023

CHARLIE ADAMS, GREENVILLE

“We were activists. We were rabblerousers, and we didn’t give a damn. A lot of people didn’t like us. That was then, and we managed to get away with it without being shot. And we’re still here.”

Charlie Adams laughs when he talks about how the founders of the Pamlico-Tar River Foundation were perceived by the general public back in 1981. Their ideas weren’t popular, even though most people paying attention could see the issues facing the Pamlico River.

“At that time, we thought it was sedimentation, and just ignorance, particularly non-point source pollution and point-source pollution — that was awful back then,” Adams said. “Of course, the Texasgulf people wanted a new mine permit and, boy, did we put them through their paces. Initially, it was kind of something that we just felt we had to do. Texasgulf was going to take the freshwater under the ground and turn our river into something it wasn’t. And we fought them tooth and nail.”

It was one of the issues that galvanized river-lovers, gathering a community of likeminded people together to start a grassroots movement on the banks of the Pamlico. Ultimately, PTRF would be a major factor in major modifications to the Texasgulf operation, including a tremendous reduction in the discharge of process wastewater into the river, and the implementation of the company’s wastewater recycling system.

What brought them together was their passion for the river.

“Honest to God, we never had a meeting that lasted less than two hours,” Adams laughed. “Somebody said ‘Let’s have an oyster roast,’ so we did; somebody said, ‘Let’s do a newsletter,’ so we did; somebody said, ‘Do a slideshow of all the problems with the river,’ so we did. I am proud that, most of all, that we did all that.”

It was brainstorming how to make the public aware of PTRF’s mission that prompted the first PTRF Oyster Roast.

“Everybody likes oysters, but people rarely think of where they come from,” Adams said. “When we cranked up the Oyster Roast in 1986 or ’87, I think that was the key to getting us off the ground.”

The Oyster Roast became a major fundraiser for PTRF and remains one today for Sound Rivers, in addition to being a signature annual event for the City of Washington.

And it was brainstorming how to educate current and future generations about local waterways and the threats they face that prompted PTRF founders and members to plant the seed for an estuarine resource center. The PTRF board, at the time, asked for, and received funding, through the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership for a feasibility study for a one-of-a-kind museum.

“We managed to snooker away a few dollars for a proposal to do the Estuarium. Anyway, long story, short — we did the Estuarium,” Adams laughed.

But some people’s perception of PTRF as “rabblerousers” deterred other, much-needed supporters from signing on with the project, according to Adams.

“There was a resistance, and when we finally had the Chamber of Commerce on board, if we had to take a back seat, then that’s what we did,” Adams said.

Passion for the Pamlico, education about the importance of its health and a lot of good intentions were the foundations of the organization that has become a powerful and respected advocate for waterways covering nearly 24% of the state of North Carolina.

“We tried to put together a group of people who represented the whole ball of wax that goes into the why you love the river — it ain’t about a bunch of white people with houses on the riverside. It’s also about the people having sufficient fishing up in Chicod Creek,” Adams said.

Adams own Pamlico roots go back to the river cottage his grandfather built on Broad Creek in 1954. He has no recollection of when he met the boys who would later become the founders of PTRF in 1981, but they all met on the river — fishing, swimming, boating, skiing through the summers — and he was a natural fit for the cause. He still is today.

“Swimming, fishing, all those things that drew me to it, a gorgeous May afternoon on my boat, I wouldn’t give it up for nothing,” Adams said. “Thank the Lord, somebody heard us.”

40 Stories, 40 years: Harrison Marks

March 20, 2023

HARRISON MARKS, WINSTON-SALEM

When Harrison Marks applied for the job as executive director of the Pamlico-Tar River Foundation, he was returning to his environmental roots. At Dartmouth College, he’d done environmental research on heavy metals and was heavily involved in the Dartmouth Outing Club, the oldest and largest collegiate club in the country, emphasizing outdoor recreation and environmental stewardship.

What followed college, however, was a career in banking.

“I spent my whole working career, until 2005, in banking institutions. I took an early retirement, I took a couple of years off, but I went back to work after the 2008 economic meltdown, until 2013. Then we moved back to New Bern, and I thought, ‘I’m too young to not do anything,’” he laughed.

Marks believes it was the sales pitch in his cover letter that got him an interview, but it was the combination of his passion for the environment and his background in business that got him hired.

“It was challenging. (Now Executive Director Heather Deck) certainly had all the environmental knowledge that the organization needed,” Marks said. “And I liked the challenge. I liked working on something that really mattered to me.”

When Marks came aboard in 2013, the battle to keep a limestone mining company from discharging up to 10 million gallons of fresh water per day into the brackish headwaters of Blounts Creek was ramping up.

“The first thing that I went to was a public hearing that was at the community college — I don’t even know that I’d been hired yet, but that’s was what was going on then, and I guess it’s still going on,” he said.

He found that in the nonprofit world, especially that of an environmental nonprofit, things were a bit different on the non-corporate side.

“Having come from a company — which I felt like for most of my career was pretty highly ethical — I was surprised that some companies were not open to discussion or reasonableness, and it was often necessary to litigate. I thought it would be possible to come up with reasonable solutions, but I found out really quickly that they weren’t interested in doing anything about the pollution they were creating. I thought, ‘Surely they would see reason,’” he said. “But I think the biggest surprise was how difficult it was to raise money. We’ve been fortunate with grants. Coming from a large organization like Wachovia, spending $5,000 wasn’t something you really thought about. But spending $500 at an environmental nonprofit is something you really have think about. Every gift matters. We know that Americans give a lot of money to charities, but to environmental nonprofits, it’s considerably less. It’s a little less tangible — the work of environmental organizations like Sound Rivers do — but it’s vitally important.”

Though at the helm of Sound Rivers for a short four years, Marks’ mark on the organization is significant: it was he who pushed the idea of PTRF joining forces with the Neuse River Foundation to form Sound Rivers, then oversaw the merger of two of North Carolina’s oldest grassroots conservation organizations.

“I talked about it with (then-PTRF Board President) Jerry Eatman, then met with Jim Kellenberger, who was the president of Neuse River Foundation,” Marks said. “I went to Oriental to meet Jim, and Jim, initially, wasn’t particularly interested.”

That changed during their meeting, when Marks pulled out a map of eastern North Carolina’s waterways.

“As we looked at the map together, Jim realized what it meant and what the organization could be, and he got on board. Then it was a matter of convincing both boards,” Marks laughed.

There were committee meetings held on neutral ground in Goldsboro and public meetings held with PTRF and NRF membership. Marks’ career in banking, overseeing several mergers, meant he was the ideal person to the lead the merger of PTRF and NRF to become a powerful advocate for waterways covering nearly a quarter of the state.

That Sound Rivers is thriving after 40 years, Marks credits Sound Rivers’ supporters, as well as the leadership of Deck after his retirement in 2017.

“It was clear to me that Heather was the right person for executive director. She worried about all the things an executive director does, so I told her ‘You may as well be executive director,’” he laughed. “Forty years is really impressive, and I think it’s a credit to the people of New Bern and Washington. I think the people who got it started, people like Dick Leach and Grace (Evans) and others that were there at the beginning — the fact that they saw the need, started it and kept it going for 40 years — and 40 years later, they’re still a voice for the river.”

After retiring, Harrison and his wife, Suzie, spent two years on their 38-foot Cabo Rico, sailing as far north as Maine and as far south as the Bahamas, before landing permanently in Winston-Salem.